Remembering Justice John Paul Stevens (JD ’47)

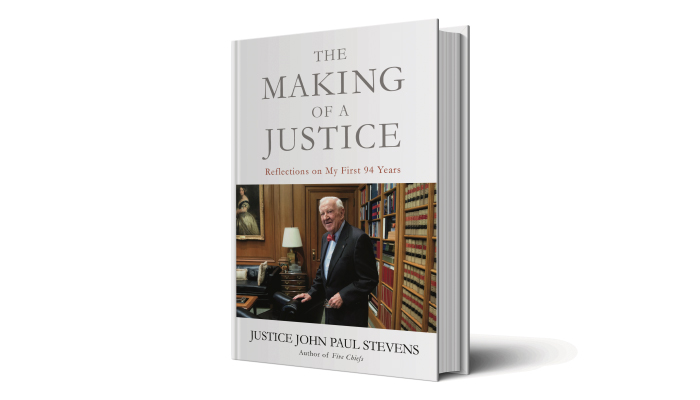

A lawyer’s most valuable asset is his or her reputation for integrity,” John Paul Stevens wrote in his recent memoir, The Making of a Justice: Reflections on My First 94 Years. Justice Stevens, ...

03.16.2020

Public Interest Alumni books nlawproud

Because I intended to practice law in Chicago, I thought it would be wise to obtain my legal education at either the University of Chicago or Northwestern. I chose Northwestern partly because my father had made the same choice when John Henry Wigmore was the dean and partly because I had already spent so many years as a student in schools affiliated with the University of Chicago that I thought a new environment would be healthy. At that time, both schools, like most of the leading law schools in the country, gave students the opportunity to graduate after only two calendar years of study; each year included a third “semester” of study instead of a vacation during the summer months.

There were only about sixty students — all men — in the class that enrolled in the fall of 1945. All of us fit comfortably in Booth Hall, a tiered classroom in which we all looked down at our professor. Leon Green, the dean, taught the torts course, and Harold Havighurst, who was to become dean after Leon retired, taught us contracts. In both courses we used casebooks prepared by our teachers. Instead of organizing the subject by studying cases involving one rule after another, the books included separate chapters for cases involving different types of fact patterns. Chapter 2 of the torts casebook was titled “Threats, Insults, Blows, Attacks, Fights, Restraints, Nervous Shocks,” and the contracts casebook contained four parts: “Services,” “Gratuities,” “Loans,” and “Contracts for the Sale of Goods.” Their approach stressed the importance of a thorough understanding of the facts that had given rise to disputes and identifying the decision-maker — usually either the judge or the jury, but often either a federal or a state judge, or a corporate executive rather than the directors or the shareholders — who should resolve the issues in the case. Dean Green frequently contrasted the approach adopted at Yale, where he had previously taught, and Northwestern to the rule-oriented approach followed at Harvard and Michigan. I have sometimes thought that the emphasis on facts and procedure instead of generally applicable substantive rules provided us with a vertical rather than a horizontal legal education.

It is perhaps of note that the Constitution principally identifies the decision-makers — the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary — rather than the rules that govern our behavior, with a few exceptions (for example, ex post facto laws are taboo). It tells us who shall make new rules and how to do so.

The torts class was also unique because Dean Green required the student discussing a case to stand while stating the case and answering his questions. In his view it was important for lawyers to be able to think on their feet. He had written extensively and critically about the doctrine of proximate cause, which he believed did more to confuse than to help judges analyze cases. In his opinion it made more sense to begin the analysis of a tort case by defining the duty that the defendant owed to the plaintiff rather than the remoteness or the proximity of the causal connection between the defendant’s conduct and the plaintiff’s injury. The dean was also a strict disciplinarian; when he learned that my friends Art Seder, Dick Cooper, Bud Wilson, and I played a few hands of bridge while eating our lunch in the basement, he concluded that card games and studying law did not belong in the same building and put an end to our games.

Unlike at most leading law schools today, in the entire Northwestern faculty when I was a student there were only about a dozen teachers, including two or three practicing lawyers who taught on a part-time basis. I was favorably impressed by each of them.

Nathaniel Nathanson, who taught constitutional law, was a few days late arriving back in Chicago after completing his wartime job with the Office of Price Administration. The students named his class “Nate’s Mystery Hour” because his discussions raised so many questions that he let the students try to answer for themselves. I think we spent several weeks discussing Chief Justice Marshall’s opinion in Marbury v. Madison. We had no trouble understanding the proposition that the Supreme Court has the power to decide that an Act of Congress is unconstitutional, but I am not sure we understood why Congress lacked the power to authorize the Court to grant a writ of mandamus ordering the Secretary of State to deliver Marbury’s commission as a judge. What I best remember about Nat’s teaching is his repeated admonition to “beware of glittering generalities.” That advice, which he may well have learned from clerking for Justice Louis Brandeis, is consistent with the basic principle of judicial restraint that Brandeis described in his separate opinion in Ashwander v. TVA1 : The Court should avoid deciding cases on constitutional grounds whenever possible, and when it is necessary to reach a constitutional issue, the Court should decide no more than is necessary to dispose of the case. Nat and his former boss would both have disagreed with the unnecessarily broad holding in Citizens United v. FEC, 2 a decision I return to in later chapters.

Our discussion of Chief Justice William Howard Taft’s famous opinion in Myers v. United States3 was memorable for several reasons. In that case, by a six-to-three vote, the Court held that a statute prohibiting the president from discharging postmasters without cause was unconstitutional. The author of the opinion was the only former president of the United States to sit on the Court. The dissenters were Justices Holmes, Brandeis, and McReynolds, each of whom wrote a separate opinion.

Relying heavily on a detailed discussion of history — including the Senate’s acquittal of President Andrew Johnson after the Civil War — Taft reasoned that the statute impermissibly limited the power of the executive granted by Article II of the Constitution. In their dissents, both Holmes and Brandeis argued that the congressional power to create a post office included the lesser power to protect postmasters from discharge without cause. Just a few years later, in a challenge to President Roosevelt’s attempted removal of a member of the Federal Trade Commission, the Court unanimously upheld the statutory provision that protected the commissioner from discharge without cause. Myers stands out in my memory because Nat insisted that we understand the competing arguments instead of casually assuming that the case had been wrongly decided because both Brandeis and Holmes had dissented and because the Court later unanimously held that President Roosevelt lacked the power to remove a member of the Federal Trade Commission without cause.

Homer Carey, who taught the courses in real property and future interests, sometimes spent class time giving us advice about practical aspects of the practice of law. On one of those occasions he commented on the importance of adopting some unique practice that would enhance the likelihood that potential clients would recognize and remember your name — his specific suggestion was to use green ink when signing letters or pleadings. The green ink idea did not appeal to me, but his suggestion made me realize that “John Stevens” was not much more unique than “John Smith” and prompted me to add my middle name to my signature. I don’t know whether my new practice of including my middle name ever got me any law business, but it did prompt fairly frequent questions about whether I had been named after naval hero John Paul Jones. My truthful answer to those queries was that I had no idea why my parents picked either of my given names.

Two lessons that I learned in Jim Rahl’s course on antitrust law merit special comment. First, sometimes the text of a federal statute cannot be read literally. Section One of the Sherman Act proscribes “every” contract in restraint of trade. As Justice Brandeis cogently explained in Chicago Board of Trade v. United States, 4 every enforceable contract restrains trade; indeed, that is the very purpose of an enforceable contract. Accordingly, the statute must be read as prohibiting only unreasonable restraints of trade. Second, the so-called rule of reason that the Court adopted to avoid the problem created by a literal reading of the statutory text also has a narrower scope than the name of the rule suggests. It does not protect any rule that a judge might consider reasonable, but only those rules that do not have an adverse effect on competition in a free market.

Brunson MacChesney, who taught the course in agency, did not finish his wartime work in Washington until after courses began. After only a few days of teaching, he arrived in class wearing the large, elaborately ribboned medal awarded by the French government to recipients of the Legion of Honor. Instead of immediately explaining his unusually distracting attire, it was only at the end of the class that he told us that French custom, or perhaps some provision of French law, included a requirement that every recipient of the medal wear it in public the day after it was awarded. The veterans in the class might have been more favorably impressed if he had provided us with that explanation immediately. Sometimes the timing of an explanation may be more important than its content.

Fred Inbau, who taught evidence and criminal law, had written extensively about the admissibility of confessions. One of his writings was cited by Chief Justice Warren in Miranda v. Arizona. 5 He was well liked by his students who often called him “Fearless Fred” or “Hanging Fred” because they thought of him (somewhat unfairly) as favoring unduly strict enforcement of the criminal law. I have no memory of any discussion of either the wisdom or the constitutionality of the death penalty in any of his classes.

Walter Schaefer, who had gained widespread respect for his work with Albert E. Jenner in modernizing the Illinois rules of Civil Procedure, taught us that subject. He later was closely associated with Adlai Stevenson when he was the Governor of Illinois and when he was twice defeated by General Eisenhower in presidential elections. Wally also became a highly respected justice of the Illinois Supreme Court.

During our senior year, Art Seder and I served as coeditors-in-chief of what was then named the Illinois Law Review. Our editions included several pieces discussing the then recent Taft-Hartley Amendments to the National Labor Relations Act, and a comment that I wrote about price fixing in the movie industry. My work on that comment — which principally discussed Judge Learned Hand’s opinion in United States v. Paramount Pictures — played an important role in developing my special interest in antitrust law.

In the summer of 1947, Art and I had a meeting in our law review office with the two members of the faculty whom I have not yet mentioned. Willard Wirtz, who later served as secretary of labor under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, had begun his teaching career at the University of Iowa Law School when Wiley Rutledge was the dean; he and Rutledge remained close friends after Rutledge became a federal judge. Willard Pedrick, who taught classes in both torts and federal taxation, had been a law clerk for Fred Vinson when he was a judge on the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. At our meeting, they informed us that Congress had enacted a statute authorizing Supreme Court justices to hire additional clerks for the terms beginning that October and thereafter. They were relatively certain that Vinson and Rutledge would hire applicants whom they recommended. The job with Rutledge would be for the October 1947 term, and the job with the chief justice would be for two years beginning in October 1948. The professors told us that they planned to recommend us for the two jobs, but wanted us to decide which job each of us would apply for. We both preferred the Rutledge option because we were interested in entering practice as promptly as possible. Because the professors considered us equally well qualified, we confronted a potential deadlock. Accordingly, we flipped a coin. I won and Justice Rutledge did hire me without an interview. I was permitted to depart for Washington without taking the final exam in the course on federal taxation and without attending the graduation exercises. Art taught in the law school for a year before beginning his clerkship with the chief justice.

Excerpted from The Making of a Justice: Reflections on My First 94 Years by Justice John Paul Stevens. Copyright © 2019. Available from Little, Brown and Company, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

A lawyer’s most valuable asset is his or her reputation for integrity,” John Paul Stevens wrote in his recent memoir, The Making of a Justice: Reflections on My First 94 Years. Justice Stevens, ...

The newest collection in the Pritzker Legal Research Center doesn’t contain a single book, journal or article. Instead, the Law School library has been hard at work archiving records of a ...

Eleanor Kittilstad (JD ’18) has been chosen as a 2018 Skadden Fellow. Upon graduation, she will work for Equip for Equality, a Chicago-based advocacy organization providing legal services to ...